Me sorprende el fair value que le dan a UNH, no porque yo tengo la más remota idea de si es acertado o no, si no por lo abultado del descuento con el que se supone que cotiza.

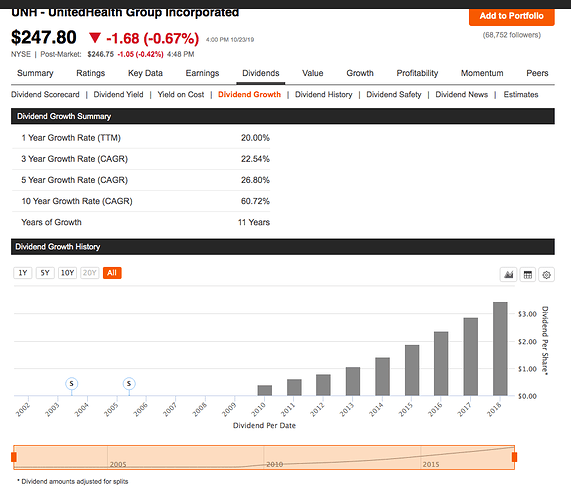

El dividendo es bajo, 1,7%, pero es que el aumento es brutal en los últimos 3-5-10 años.

A mi solo 3 ![]()

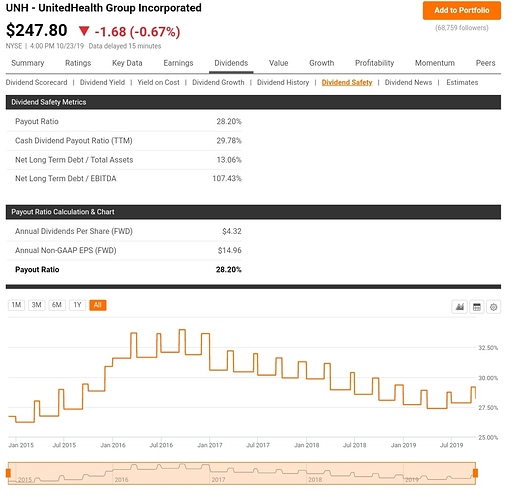

Lo interesante de UNH es ver la gráfica del payout al lado, no es como en AVGO por ejemplo que las subidas tan fuertes son a base de incrementar payout considerablemente.

Cual será la tercera? ![]()

Estan las 3 en la cartera que publique en mi hilo ![]()

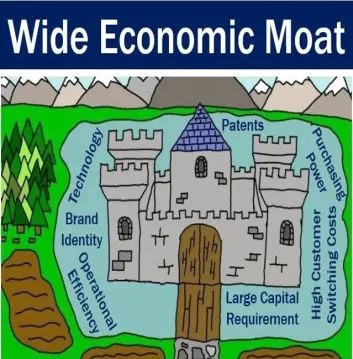

Yo con los moats que da m* a veces me quedo con cara de tonto. Por ejemplo, no entiendo como berkshire hathaway puede tener Wide moat si no es más que un “fondo” que cualquiera puede replicar. Lo entendería antes cuando compraba negocios pequeños, pero ahora (casi) todo lo que compra buffet lo puedo comprar yo (multiplicado por 0.0000000000000000001, claro).

Aqui lo explican

16/08/2019

Berkshire’s wide economic moat is more than just a sum of its parts, although the parts that make up the whole of the firm are fairly moaty in their own regard. The company’s insurance operations–Geico, Berkshire Hathaway Reinsurance Group, or BHRG, and Berkshire Hathaway Primary Group, or BHPG–remain important contributors to the overall business. Not only do they account for 25%-35% of Berkshire’s pretax earnings (and close to 40% of our current valuation of the firm owing to the firm being overcapitalized and maintaining a larger than normal equity investment portfolio for a property and casualty insurer), but they also generate low-cost float. These temporary cash holdings, which arise from premiums being collected in advance of future claims, have allowed Berkshire to generate additional returns as the company has invested these funds in assets that are commensurate with the duration of the business that is being underwritten, and have tended to come at little to no cost to Berkshire given the company’s proclivity for generating underwriting gains the past several decades. That said, from an economic moat perspective, we don’t believe the insurance industry is particularly conducive to the development of sustainable competitive advantages. While there are some high-quality companies operating in the industry (with Berkshire having some of the best operators in the different segments where it competes), the product that insurers sell is basically a commodity, with excess returns being difficult to achieve on a consistent basis.

Buyers of insurance are not inclined to pay a premium for brands, and the products themselves are easily replicable. Competition among insurance firms is fierce, and participants have been known to slash prices or simply undercut competitors to gain market share. Insurance is also one of the few industries where the cost of goods sold (signified by claims) may not be known for years, providing an incentive for companies to sacrifice long-term profitability in favor of near-term growth. In reinsurance, this dynamic can be even more pronounced, as losses in this business tend to be large in nature and may not be realized for years after a policy is written. Insurers can, however, develop sustainable cost advantages by either focusing on less commodified areas of the market or by developing efficient and/or scalable distribution platforms. What they can’t do is gain a sustainable competitive advantage through investing, even when gains are the result of the investing prowess of someone like Buffett. We believe insurers that consistently achieve positive underwriting profitability are better bets in the long run, as insurance profitability tends to be more sustainable than investment income.

Given the continued strong growth of its auto insurance operations, and the more meager growth in its reinsurance operations, Geico has become the largest generator of earned premiums for Berkshire. The auto insurer has made great strides with its direct-selling operations, moving from its position as the seventh-largest U.S. private auto insurance underwriter two decades ago (with 3.6% market share) to the second-largest at the end of 2018, with 13.4% of the market compared with industry leader State Farm at 17.1%. Much like its closest competitor, Progressive (which generated 11.0% of written premiums last year), Geico has set itself apart from the rest of the industry by its scale in the direct response channel. While scaling is typically difficult for insurance companies, personal line insurers like Geico and Progressive have been better at spreading fixed costs over a wider base, as their business models do not require as much human capital and specialized underwriters as other insurance lines. Given the similarity in their auto insurance operations, with both firms at the forefront of the shift into non-agent-derived business, as well as the level and consistency of each insurer’s underwriting profitability the past decade (with Geico producing an average annual combined ratio, including the impact of hurricanes and other natural disasters, of 95.8% during 2009-18 compared with Progressive at 93.3%), we believe that Geico, much like Progressive, has a narrow economic moat.

With regards to Berkshire’s reinsurance arm–BHRG–we believe that at best it has a narrow economic moat around its operations. For a premium, reinsurers assume all or part of an insurance or reinsurance policy written by another insurer. While any insurance company can underwrite reinsurance, a handful of larger companies–Munich Re, Swiss Re, Berkshire Hathaway, Hannover Rueck, and SCOR SE–hold sway over the lion’s share of global premiums written. The policies underwritten by reinsurers often contain large long-tail risks that few companies have the capacity to endure and, when priced appropriately, can generate favorable long-term returns. That said, reinsurers compete almost exclusively on price and capital strength, making it almost impossible to build structural cost advantages. Losses in the reinsurance market are also lumpy and may not be realized for years after a policy is written, magnifying the importance of disciplined and accurate underwriting skills. While we don’t normally view reinsurers as benefiting from favorable competitive positions, there are some specialty lines where a long history of underwriting incidence and/or from unique relationships can allow firms to build sustainable competitive advantages. We believe that Berkshire’s reinsurance operations are unique. The company’s overall balance sheet strength makes it capable of taking on large amounts of super-catastrophe underwriting (covering events like terrorism and natural catastrophes) that few companies have the capacity to endure. Historically, it has also had the luxury of walking away from business when an appropriate premium cannot be obtained, something its publicly traded peers cannot always do. However, its underwriting profitability has been less consistent because of the nature of the risks that it is underwriting and is much narrower than Berkshire’s other insurance businesses. The company sticks with reinsurance, though, even if it can be unprofitable from time to time, because it generates float that can be invested for longer periods of time than short-tail lines such as auto insurance.

As for BHPG, which has been Berkshire’s most profitable insurance business the past 20 years, we believe the segment has developed a narrow economic moat. What is all the more remarkable about this is that BHPG is a conglomeration of several different insurance operations, including National Indemnity’s primary group, Berkshire Hathaway Homestate Companies, Berkshire Hathaway Specialty Insurance, Medical Protective Company, U.S. Investment Corporation, Berkshire Hathaway Guard Insurance Companies, and Applied Underwriters, which Berkshire is in the process of divesting. These entities offer coverage as varied as workers’ compensation and commercial auto and property coverage to excess and surplus lines. By focusing more on specialty lines that require extensive experience or unique relationships to underwrite effectively, BHPG has been able to put together a continuous record of solid earned premium growth and underwriting profitability, which is a rarity in the insurance business (with most P&C insurers willing to take underwriting losses from time to time in order to generate earned premium growth, believing that they can make up the difference with investment gains).

Of the more than 70 noninsurance businesses that make up Berkshire’s remaining subsidiaries, Burlington Northern Santa Fe and Berkshire Hathaway Energy are usually lumped together under the company’s railroad utilities and energy segment in Berkshire’s financial statements. While their contribution to pretax earnings and our own fair value estimate for the firm are now overshadowed a bit by the newly combined manufacturing, service, and retailing segment (which rolled up Berkshire’s finance and financial products division at the end of 2018), they are far more transparent than the company’s other operating segments. On a combined basis, BNSF and BHE have generated 30%-35% of Berkshire’s pretax earnings on average and currently contribute 28% to our estimate of the company’s overall fair value.

The most interesting thing about these two businesses is that neither one was a major contributor to Berkshire’s pretax earnings just over a decade ago. Buffett’s shift into such debt-heavy capital-intensive businesses as railroads and utilities has represented a marked departure from many of Berkshire’s other acquisitions over the years, which have tended to require less ongoing capital investment and have had little to no debt and have tended to produce higher returns on average. That said, were Buffett to focus on buying more asset-light companies with fewer capital investment needs, it would have left his successors with even greater amounts of cash to have to reinvest annually in the longer term. During 2014-18, the firm generated an average of $21.8 billion annually in free cash flow. The amount of excess cash Buffett would have needed to find a home for would have been meaningfully higher had Berkshire purchased similar-size companies to BNSF and BHE with similar cash flow profiles that were not investing close to $10 billion on average annually collectively in their own property and equipment.

With BNSF, which was acquired in full in February 2010, Berkshire picked up a Class I railroad operator–an industry designation for a large operator with an extensive system of interconnected rails, yards, terminals, and expansive fleets of motive power and rolling stock. We believe that all of the major North American Class I railroads benefit from colossal barriers to entry due to their established, practically impossible-to-replicate networks of rights of way and continuously welded steel rail. While barges, ships, aircraft, and trucks also haul freight, railroads are by far the lowest-cost option when no waterway connects the origin and destination, especially for freight with low value per unit weight. Customers have few choices thus wield limited buyer power, with most Class I railroads operating as duopolies (and some being a monopoly supplier) to the end client in many markets. This provides the major North American Class I railroads with efficient scale. Believing that operators like BNSF will continue to leverage their competitive advantages of low cost and efficient scale to generate returns on invested capital in excess of their cost of capital, we have awarded them wide-moat ratings.

As for Berkshire Hathaway Energy, which Buffett built up through investments in MidAmerican Energy (supplanting a 76% equity stake taken in early 2000 with additional purchases that have raised its interest to 90.9%), PacifiCorp (acquired in full during 2005), NV Energy (acquired in full at the end of 2013), and AltaLink (acquired in full at the end of 2014), we think the business overall is endowed with a narrow economic moat. While BHE has picked up pipeline assets–which have wide-moat characteristics–the majority of its revenue and profitability (and ongoing capital investment) are driven by its three main regulated utilities: MidAmerican Energy, PacifiCorp, and NV Energy. We think that regulated utilities cannot establish more than a narrow moat around their businesses, even with their difficult-to-replicate networks of power generation, transmission, and distribution, given that their rates, as well as their returns, are set by state and federal regulators.

While Berkshire’s manufacturing, service, and retailing operations are now one of the largest contributors to pretax earnings, following the folding of the old finance and financial products segment into the MSR unit, getting a handle on the profitability (and economic moats) of the wide array of businesses (operating in more than a handful of different industries) that make up the segment is difficult at best. Unlike BNSF and BHE, both of which file quarterly and annual reports with the Securities and Exchange Commission, there is little financial information available on the firms operating in this segment. That said, given Buffett’s penchant for acquiring companies that have consistent earnings power, generate above-average returns on capital, hold little debt, and are run by solid management teams, we believe that the vast majority of the businesses that make up the segment are collectively endowed with a narrow economic moat.

We’d also note that during 2018, the five largest companies (on a pretax earnings basis) in the MSR segment–Precision Castparts, Lubrizol, Clayton Homes, Marmon, and IMC/ISCAR–accounted for more than half of the pretax earnings produced by the division. Each of these subsidiaries, by our estimates, has a fairly solid narrow moat around its operations. When combined with the next five largest subsidiaries–Shaw Industries, Forest River, Johns Manville, TTI, and MiTek Industries–the 10 subsidiaries accounted for more than 70% of the MSR segment’s pretax earnings last year, with a moat rating overall that skews to the narrow end of the spectrum. With Buffett running Berkshire on a decentralized basis, the managers of the company’s operating subsidiaries are empowered to make their own business decisions.

In most cases, the managers running Berkshire’s subsidiaries are the same individuals who sold their firms to Buffett, leaving them with a vested interest in the businesses they run. Barring a truly disruptive event in their industries, we expect these firms to continue to have the same advantages that attracted Buffett to them in the first place. That does not mean that there won’t be subsidiaries whose competitive advantages diminish over time (exemplified by the demise of the textile manufacturer that Berkshire Hathaway derives its own name from), it’s just that the large collection of moaty firms that reside within Berkshire’s manufacturing, service, and retailing operations, is more likely to maintain a narrow economic moat in aggregate, even as a few firms along the way succumb to changing competitive dynamics within their industries.

La verdad que unas partes tiene wide moat y otras solo narrow y tambien podrian haberle dado solamente narrow moat en global. Seguro que cuando la palme el abuelo le bajan de wide a narrow.

Gracias por el post, vash , pero aunque le doy vueltas a eso de cobrar las primas de seguros por anticipado, sigo sin verlo.

En cualquier caso el concepto de moat no es de aplicación a BRK, porque si cualquiera pudiese hacer la coca cola en casa con agua del grifo y mondas de patatas KO se iba a pique. Pero a BRK se la suda que todos tengamos la fórmula para ganar dinero con nuestras inversiones.

Quiero decir que no tiene competidores que quieran quitarle cuota de mercado, por lo que hablar de moat carece de sentido

Quiza la clave este en que Berkshire es irreplicable hoy dia. Cuando le preguntan a Terry Smith en las entrevistas si se puede hacer lo mismo que Warren Buffett dice que exactamente lo mismo no por el float que genera el negocio asegurador de Berkshire pero que si se pueden aplicar las mismas reglas de inversion en general.

¿Y Amgen por que no?

“As a conceptual matter, it is crazy to think that someone who buys a share of Berkshire Hathaway at $208 per share is acquiring ownership in a company that has the cash-on-hand capacity to pay out a $50 per share dividend”

Porque parece que va a crecer poco en el futuro proximo

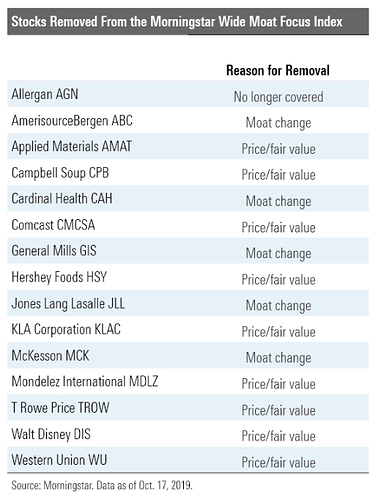

Ah en un primer momento entendi que habian bajado el Moat a Narrow a toda esta lista y estaba algo sorprendido, las sacan de su indice de Wide Moat, la gran mayoria por estar “caras”, no?

Un saludo y gracias por compartir @vash

No. El moat no tiene que ver con el precio.

Ya, de ahi mi sorpresa inicial con la imagen porque lo habia entendido mal, no alteran el Moat que les dan sino que sacan estas empresas de su indice M* Wide Moat Focus y meten las otras que ponia @anbax en el primer mensaje. Cosas que pasan por mirar directamente los datos sin ver el encabezado

El Wide Moat Focus Index de M* es como un fondo que simulan donde meten y sacan empresas. Para entrar esta claro que tienen que tener Wide Moat y ademas estar baratas pero para sacarlas pueden sacarlas porque les bajan el Moat => Moat Change o porque estan caras => Price/fair value (aunque sigan teniendo Wide Moat)

En contraposición tenemos el Alierta Economic Moat, que también puede representarse mediante un castillo (o lo que queda)