Seessel, Adam. Barron’s (Online); New York (Jul 9, 2019).

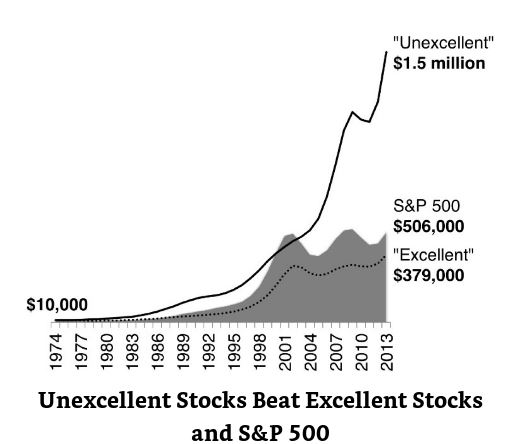

When I was a junior analyst at Sanford Bernstein nearly 25 years ago, our betters drummed into our heads that everything in the investment world went back to normal and that John Templeton was right when he said that the four most expensive words in the English language were “this time it’s different.” Bernstein had a sophisticated computer model that we referred to as the black box; its job was to tell us worker bees the most statistically cheap sectors every month. Like good worker bees, we would more or less automatically buy the stocks in those sectors and sell stocks in the most expensive sectors. The black box minted money for the firm and its clients for decades, precisely because everything did eventually return to normal. Cheap auto stocks appreciated to fair value, expensive tech stocks returned to average, and the investing world was good—safe and predictable. It was indeed dangerous to think “this time it’s different.”

Today, however, five of the world’s six largest companies by market value are tech companies. Most of them weren’t even born when Bernstein laid down its law. As for returning to normal, does anyone really believe that is going to happen, for example, to Amazon.com or Alphabet? E-commerce and digital advertising still have only a small share of their global market, despite nearly a generation of growth. Other industries—ride-sharing,onlinelending, and renewable energy—are smaller still, but also show every sign of being long-term winners. How are these sectors going to somehow revert to the mean? Conversely, how will legacy sectors that lose share to these disruptors return to their normal growth trajectory?

Digital, wireless, and other disruptive technologies are changing our economy in ways that nobody fully understands, but one thing is increasingly clear: Old-economy sectors like retail and financials are cheap not for short-term, cyclical reasons—they are cheap for long-term, secular ones. As a result, exchange-traded-fund investors should think twice before buying sectors that look statistically cheap, but are exposed to secular risk. When rebalancing portfolios, it often will be a mistake to trim the expensive sectors to buy the cheap ones. And even if an investor decides to overweight industries on the right side of history, caveat emptor: Some ETFs in growth sectors have considerably more exposure to legacy firms than others.

I am a bottom-up stockpicker, but from my days at Bernstein I understand and sympathize with those who make sector bets. Consider this a warning from your stock-picking cousin who’s spent time exploring the frontier of the early 21st century economy. Things look very different than they did 25 or even 10 years ago. Sector bets must be placed accordingly.

Retail’s challenges in the face of Amazon are well-known, but many other, less obvious sectors are at risk, as well. The energy industry, especially large, legacy fossil-fuel companies, faces multiple headwinds in the form of shale technologies, wind, and solar energy rapidly coming down the cost curve—and, of course, there’s vehicle electrification. Autos themselves have many challenges: Bloombeg Businessweek recently ran a cover story on “peak car,” calling the automobile “the killer transportation app of the 20th century.” Even sectors that many investors consider rock solid are showing signs of cracks. Legacy financials are still well loved by value investors, but financial-technology companies have gone from accounting for a zero percent share of U.S. personal loans to nearly 40% in a decade. They were born online, have slick mobile interfaces, are customer-friendly, and have much less bureaucracy than legacy banks. Quicken Loans now ranks among the nation’s largest mortgage lenders; it says you can get a Quicken mortgage two to three times faster than from a legacy bank.

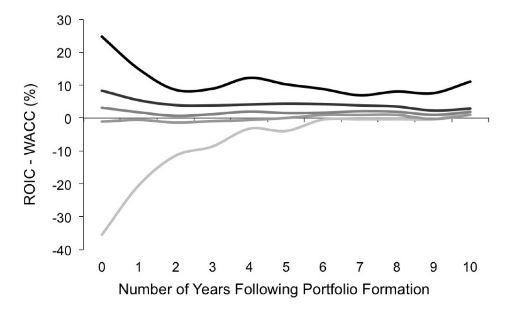

From both a top-down or a bottom-up perspective, it’s easy to see that the investment implications are profound. David Giroux, a portfolio manager for T. Rowe Price and the firm’s chief investment officer of U.S. Equity and Multi-Asset, puts each company in the S&P 500 through what he calls a secular-risk analysis four times a year. When he started the process five years ago, he and his team found that companies representing 20% of the S&P’s market capitalization faced threats from sea changes in the economy. Today, Giroux estimates, that figure is more than 30%. In a few years, he says, it could be 40% to 50%.

“When I was an associate analyst in 1998, I covered digital-imaging stocks like Xerox and Kodak, and those certainly had their challenges,” Giroux says. “But the overall disruption in the economy was not large, even when I became a portfolio manager in 2006. Since then, however, more and more companies have got caught up in secular challenges—and that trend is not abating; it’s getting stronger.”

Giroux is applying this research as the stock-picking manager of the T Rowe Price Capital Appreciation fund (ticker: PRWCX) with impressive results: Since 2006, it has delivered 108% of the market’s return after fees, despite running a balanced strategy averaging only 60% to 65% equity exposure. But his secular-risk analysis contains important information for ETF investors. One obvious implication is that ETF investors should overweight sectors that are going to be secular gainers and underweight those that are falling behind. In 1990, the information-technology sector was roughly 6% of the S&P’s market value as defined by the Global Industry Classification Standard; today, it’s 21%. Aerospace and Defense, a subgroup of GICS’ industrial sector, also has tailwinds: The number of miles flown by commercial aircraft has grown at roughly twice the rate of worldwide gross domestic product over the past 50 years, yet 80% of the world’s population has still not set foot in an airplane.

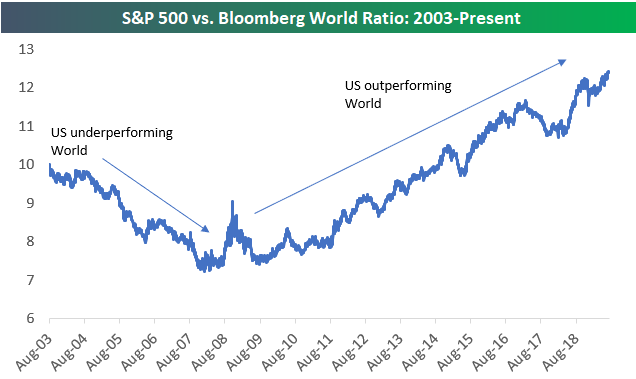

This same binary, growing-or-dying mind-set should apply when rebalancing sector allocations. Sectors that appear cheap, but are secularly disadvantaged, will get cheaper. Telecom is a good example. In the early 1990s, it was nearly 10% of the S&P’s market cap and bigger than the IT sector. Thanks to serial technological disruptions, however, what was once the nation’s communications backbone represented a mere 2% of the S&P’s market value last year. Telecom has become such a small part of the U.S. economy’s value that, last fall, S&P and MSCI, which jointly own the GICS classification system, abolished telecom as one of 11 major sectors.

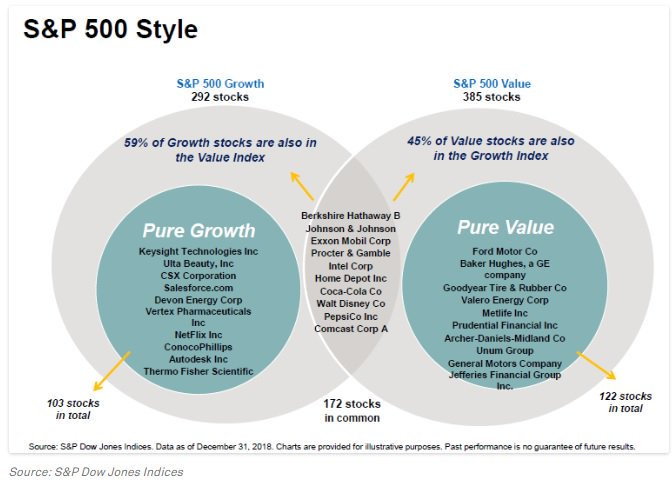

Finally, and perhaps least obviously, even if you decide to invest in secular growth sectors, it is not a good idea to blindly buy an ETF just because its name sounds like it will provide the exposure you want. Consider the ETF industry’s two biggest tech funds: Because they chose to include different underlying sectors at inception, they have had widely divergent long-term performance. Morningstar data show that a $1 million investment in the Vanguard Information Technology Index fund (VGT) would have returned an investor $5.59 million over the past 15 years—but that same $1 million in the Technology Select Sector SPDR ETF (XLK) would have returned $5.04 million, or $550,000 less. That’s a shocking gap, largely attributable to a decision made by the SPDR’s creator, State Street Global Advisors. When it created the security back in the late 1990s, State Street included the ill-fated telecom sector. Vanguard based its ETF on only the GICS IT sector—the same sector that grew from 6% to 21% of the S&P’s market cap over the past generation.

This discrepancy has been remedied; with the abolishment of the telecom sector last year, State Street now relies solely on the GICS IT sector, as does Vanguard.

For many years, the person in charge of Bernstein’s black box was CEO Lew Sanders. Sanders left the firm a decade ago and started his own shop, Sanders Capital, which now runs more than $25 billion, mostly in global equities. A year or two ago, I looked up Sanders Capital’s largest holdings. I was beginning to believe that reversion to the mean was largely defunct as an investment construct, and I suppose I wanted to check myself against the keeper of the mean-reversion flame.

Four of Sanders’ five largest positions were tech companies. These included Alphabet (GOOG) and Microsoft (MSFT), and they remain in his top five today. Both trade for mid-to-high 20s multiples of earnings, and, as such, they are definitely not statistically cheap. On the other hand, neither shows any sign of reversion to the mean. Digital advertising currently represents well under half of total worldwide marketing spend. Cloud computing currently handles only 10% to 15% of the daily IT workload. This time really does seem different.

Adam Seessel is the founder and CEO of Gravity Capital Management in New York. Gravity had a position in Alphabet when this article was published.

Email: editors@barrons.com

Credit: By Adam Seessel